Learn how to turn interviews into saleable biographical profile books. This fascinating genre is wide open to independent authors. We teach what you need to know to get started. You needn't know anyone famous, either!

How to get started writing biographical profile books

Biographical profile writing can be fascinating and profitable. While for many professional freelance writers and independent authors, it may never be part of the mix of genres and styles they work in, it's worth trying it at least once. If you have a deep curiosity about what “makes people tick,” a talent for building rapport with others, and the skill to communicate personality in well-crafted, succinct prose, you'll enjoy it, and may even make a full time living out of writing and publishing biographical profiles.

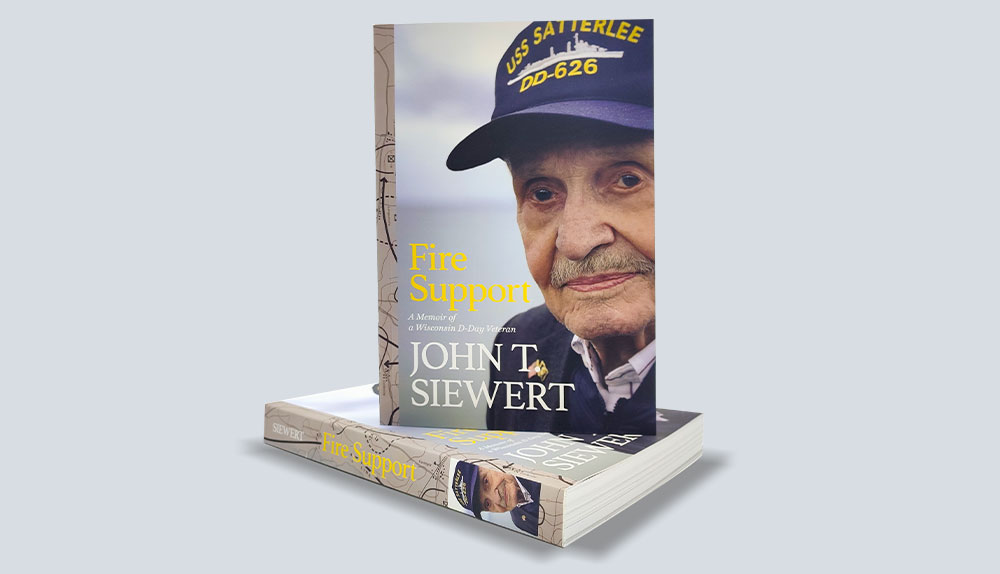

We've printed lots of extraordinary and beautiful stories in the profile genre, often in the interface between biography and memoir. Some of those have been focused on people at least famous in their field – artists, photographers, and others – but most are about people otherwise unknown; the “everyday heroes” and “secret saints” who live nevertheless fascinating and worthwhile lives. Several of these books have been successful.

So, what is a biographical profile?

Biography means writing about someone's life. That person may be dead or alive. It doesn't have to be a “cradle to the grave” story. It can focus on one aspect of that person's biography – a specific achievement or time period. When it deals with a living person and focuses on a core story rather than a complete biography, we call it a profile. In portrait painting, a ‘profile' is a view of the sitter's face, seen from one aspect only, and highlighted to expose the defining features most expressive of the subject's personality. The profile book is exactly the same, but the medium is language rather than paint. It's not a full-scale biography. Profiles focus on one aspect of the person's life and achievements, highlighting the most salient points, and attempting to reveal something of the personality behind the story.

Profiles can be about anyone with a story worth telling. We've seen successful profiles about a church minister and her outreach work; the CEO of a successful start-up; historical figures; a hotelier; a children's author; and an illustrator and artist. You can write your book about anyone at all in whose life readers would be interested or by which they'd be inspired. Often, it's better if your subject is otherwise an “unknown” as it makes them more relatable and so their story even more impactful as the reader enjoys the sensation that “it could have been me.”

Popular subjects for biographical profile books

While anyone may be a good subject for a profile book, the market or markets you are targeting – women, nostalgia, hobbies, sports fans, history buffs, etc. – will help you narrow your focus and suggest an angle. An original angle and a fresh perspective will make your book more attractive to readers. In the women's market, for example, you could highlight successful women in professions traditionally associated with men such as a female soccer coach or for the nostalgia market, you could write a profile of the oldest person in your town and the changes they have seen in their lifetime. But let's take a look at the market sectors in which it's easiest to find suitable subjects for biographical writing and in which profile books often sell well. A good indicator of whether there's a market for books on a certain topic is the number of magazines, websites, blogs, and TV programmes that cover the same subject. If these are plentiful, then it's highly likely that there'll be a book-buying public for that niche, too.

1. The hobby markets

There's a niche magazine, website, and blog for every hobby under the sun. You'll find publications for enthusiasts of woodworking, model-making, furniture restoration, doll-making, knitting, needlepoint, pet-keeping and showing, indoor gardening, outdoor gardening, flower-arranging, cooking, bird watching, hunting and fishing to motor racing, rock climbing, scuba diving, hiking and camping, mountain biking, video gaming, role-playing and war-gaming, cos-play, comics, reading clubs, amateur dramatics, painting, music, dance, and everything in-between. The collecting sub-niches are almost infinite: from antiques, dolls, buttons, vintage clothes, suitcases, cigarette cards, military gear, model cars, and first editions to Pokémon, Star Wars memorabilia, action figures, and more.

An advantage of the hobby market is that you can easily find someone in your locality with a passionate interest in their hobby. Often, enthusiastic hobbyists are also wonderfully colorful and eccentric characters with great stories to tell. Most will be only too happy to give interviews in exchange for the pleasure of seeing themselves between the covers of a book and to have the opportunity to promote their hobby.

2. Trades and professions

You'll also discover that there are a ton of journals, websites, blogs and often TV shows for every trade, business, and profession under the sun. Anyone with a useful insight to offer: an innovator in their field; the wisdom of someone looking back on a lifetime's experience; insider secrets of a successful entrepreneur; or an unusual person to find in that business or niche could all make the starting point for intriguing and informative biographical profile books directed to the trade and industry markets.

3. Amateur and professional sports

Sport is always popular. The sporting press, sports news websites, and the blogs of any number of associations and even fan clubs, not to mention the massive TV coverage, bear ample witness to the popularity of this niche. While baseball, football, hockey, and basketball are the obvious sports, you'll find an audience for swimming, gymnastics, running, cycling, martial arts, bowling, and lacrosse. What about digging up interesting people from the fringes of the sport world? Think curling, obstacle racing, club swinging, rope climbing, synchronized swimming, and tandem racing, to name only a few.

When thinking about who you might approach for an interview, the subject needn't be a player. A professional or amateur coach may have interesting insights to share, or parents of kids into the sport could have a unique perspective; maybe a super-dedicated fan who's never missed a game in thirty years; the oldest or the youngest; the CEO of a company that manufactures specialist kit could provide a new angle; or one of the many talented differently abled sports people, for example. Don't stop at the obvious. The more unusual and fresh your idea, the better your chances of writing an interesting and original book.

4. Health professions, social care, and charities

Stories of anyone working “on the front line” to make life better for those worse off are always worth sharing and often sell extremely well. The inside stories of people risking their lives daily to help others make great reading. Besides doctors, nurses, and other healthcare workers, think about mountain rescue, firefighters, or famine relief, for example. But don't stop there. Conservation workers, at home or abroad, professional or voluntary, may have great stories to share. What about the family on your block who have fostered dozens of kids from broken homes? Or the staff of an animal charity that rescues, rehabilitates, and rehouses abused and abandoned pets? Those are just a few ideas to get you thinking. The possibilities are endless.

5. The 'paying it forward,' story

The last category is the kind of story which shares the contribution made by a person who has “been through the mill,” come out the other side, and dedicated their life to helping others confronting the same problems. These biographical profile books can be deeply moving and inspiring. Examples might be a cancer survivor who offers counseling and advice to other sufferers; an ex-homeless person who supports the destitute in rebuilding their lives; the young mother whose child was killed by a drunken driver and now leads a campaign for alcohol awareness; or the promising college hockey player who lost a leg in an accident and now coaches disabled kids. Again, a little research – try the newspaper archives in your local library to get started as local papers often run human interest stories of this kind – will turn up innumerable people whose courage and determination to overcome tragedy leads them to a life dedicated to helping others.

Biographies in this category are always good sellers if you can write them well. But they're undoubtedly the most challenging to do. They need considerable sensibility and thoughtful treatment, not to mention finely tuned writing skills and the ability to tell the story with clarity and honesty without falling into sentimentalism, sensationalism, or cliché.

Finding your subject for a biographical profile book

Where do you find a subject for your profile book? The honest answer is that no hard-and-fast rules exist to guide you, but the possibilities are many. Local and national newspapers are an excellent source of potential subjects. In most cases, you'll need to dig much deeper than the front page news. Scour the specialist sections and human interest stories to find likely subjects you could chase up.

Never ignore the agony columns in popular magazines. The place where people share their personal problems, tragedies, and successes is often a good source of material. Remember that the subject of a profile piece already published in a magazine or featured in a news story has already proved their “viability” and may be an excellent subject for an expanded book-length treatment if you can see a different and original angle on the same story. You also know that the person is willing to give an interview and that at least one editor has already considered the subject's story worth sharing; which means that your book most likely has a ready-made audience once it's written, printed, and published.

Attending meetings, conferences, and events are another potential way to uncover a subject with a story worth telling. If you can't do it in person, don't ignore YouTube and other online venues. Ted and TedX talks could well give you several fascinating leads to follow up, not to mention mining your social media for interesting characters who may be willing to give you an interview.

Often, you'll find the subject for a great profile piece presents themselves unexpectedly in the course of your daily life. A person you meet by chance, or hear about through a casual conversation with friends, or encounter in some other way when you weren't scouting for a lead. Remember, the difference between a successful writer and anyone else isn't that they have more opportunities, it's that they look out for them and learn to recognize them as they come round.

Getting set up for biographical profile interviews

Once you've identified a potential subject for your profile, you must do a little background research. You may use the newspapers, magazines, people who know the person, libraries, Google, social media. But your research must have a clear focus. So, choose that one fascinating aspect of the subject's life or biography — the thing that makes them interesting and stands out from the crowd — and gear all your research to highlighting that core factor.

As you uncover material about your subject, make notes and think about questions you can ask, which will encourage them to tell you their most revealing and interesting stories. Also, if you can demonstrate that you have some knowledge and enthusiasm in common, then your subject will feel easier opening up to you.

Once your research is complete and you've a list of potential questions, you must approach the person to request an interview. You should contact them first, either by letter, email, or even on social media or by telephone if it seems appropriate. On first contact, explain briefly that you're a freelance writer and that you'd like to interview them for a profile book aimed at whichever market it is you've researched, and ask if they would be willing to give an interview.

You may want to have the following information at hand:

- Any previous publication credits in your name, details of your qualifications and experience, your author website, etc.

- How you found out about the person and some evidence that you have done initial research about them.

- Why you think they'd make a great subject and a few short ideas about the treatment or ‘angle' that you have in mind

- How long do you expect the interview or interviews to take? As you'll be focusing on only a narrow aspect of the subject's life, an hour to an hour and a half at a time should be enough. It's better to do a series of shorter interviews than risk tiring both yourself and your subject out. An hour to an hour and a half is about right to give you both time to relax into the process and for your subject to begin to open up without exhausting them.

Be prepared to answer questions and concerns, too. Once you have the subject's consent, you can set up the interview or interviews. Be flexible and allow your subject to decide the time and place within reason. If you can't meet in person — either because the subject doesn't want to or for logistical reasons — arrange an interview by telephone, Skype, Zoom, Google Meets, or some other online channel.

When you fix the appointment, it's important to set a few ground rules to make everything clear for both parties. So, remind them how long you expect the interview to take, that you'll need their consent to record the interview, that you'll need peace and quiet, and that you'll bring (or send) a consent form for them to sign which details how the material will be used.

All profile books need to be illustrated with photographs, both of the subject and any other relevant subjects such as documents, places, and more, so you must get the subject's consent for that, too. If you have a first-class camera and reasonable expertise, you can take the photographs yourself. Otherwise, you'll need to hire a professional and factor the cost into your final budget for the project.

If you plan to make a career out of biographical and profile writing, you'd do well to invest in a good camera and a range of lenses, filters, and a short course in photography and digital manipulation. The photos of your subject should be more than a head-and-shoulders portrait. Try to capture something of the ambience of the person's home if that's where the interviews take place, or their working environment, or a few shots of them engaging in whatever activity it is for which they're known.

Don't forget, whether you're taking the photographs yourself or using those for which you've paid a professional photographer, that you must make sure the files you submit to us for printing (or any other printer you choose) conform exactly to the guidelines: so, format them at reasonably large dimensions, use the CMYK color space, and make sure the resolution is at least 300 DPI. You should also write explanatory captions to accompany the images.

Conducting profile interviews

Take time beforehand to be sure you know where the meeting place is and how to get there. Aim to arrive a few minutes early and make sure you dress appropriately both for the person you're interviewing and for the venue in which you meet. Make a checklist before you leave to be sure not to find yourself in difficulty or embarrassment later. Be as calm, prompt, and professional as you can.

Remember that the person you're interviewing may be nervous and a little apprehensive, especially if this is the first experience that they've had of giving an interview. Make sure that you put them at their ease with eye contact, a generous smile, and a calm sense that you know what you're doing. Ask them if there's anything they need before you get started — a cushion or a glass of water, for example.

We would counsel against looking at your notes, or taking new notes, during the meeting if you can avoid it. Try to memorize key facts and your main questions beforehand. You need to be ready to give your attention to your subject and show an active interest in what they say. You're there to listen.

If the interviews take place in the subject's home, or garden, perhaps their office, or even a favorite bar, restaurant, or café, make mental notes of the decor and atmosphere and what that says about the interviewee's personality. This is all great information you can use later to add color and immediacy to the interview when you write up your book.

Don't fire straight into the most difficult questions, particularly if the subject is nervous or shy. Start with a compliment or two and some general conversation to help put them at their ease. And remember that your job is not to do all the talking! You need to find the key that will unlock the door to their enthusiasm and passion and get them to share their memories, thoughts, ideas, knowledge, and feelings with their guard a little lowered. Building rapport from the get-go is vital to a good interview technique.

That said, remember that this is a guided interview. You must avoid your subject rambling or going off at tangents, which takes you away from the core focus of your book. An hour and a half will be gone in the blinking of the proverbial eye. We promise you. Make sure every moment counts.

Recording the interview

We mentioned recording the interview earlier. It's an excellent idea as it means you can check that you've remembered everything clearly; it serves as a vivid reminder of your subject, their voice, mannerisms and personality; and it helps you to focus on listening and responding rather than taking notes during the interview. But occasionally you may have a subject who is opposed to being recorded and cannot be swayed. In such a case, don't push too hard. It's a useful tool, but it's not necessary.

What you use to record the interview is up to you. Almost any smartphone these days will probably serve your purposes. But you may wish to invest in a specialist sound recorder with a high-quality microphone.

Back in the day, writers and journalists used to carry around a so-called ‘portable' tape recorder. It was, strictly, portable; but it weighed a ton, had to be hauled around on a long leather strap, was extremely obtrusive, had loud, “clicky” controls, and you had to flip the tape over halfway through, often breaking the subject's flow.

The point of that story is not mere nostalgia. It's showing that you needn't fuss too much about the technology. If it records what's said, it'll do the job. And anything you use today will be less intrusive than those old machines!

How to deal with sensitive material if it comes up

It may well happen — depending on the nature of the story — that your subject tells more, and from a deeper place, than they'd be comfortable for you to publish, especially if you've built a strong and genuine rapport with them. They may also share information and facts about other people that you won't be able to use. The situation requires discernment, sensibility, and honesty on your part.

If there's anything you're not sure you should use — no matter if it would make great copy! — you must ask. In certain circumstances, you may also need to take legal advice. But we must emphasize that such a situation is very rare. In ninety-nine per cent of cases, the subject's permission is all you need. Just be sure to get it in writing.

The only point to add is to always conduct your interviews with goodwill and integrity. In the contemporary cultural climate, these virtues may seem dated, but their value is without measure. Be honest and be kind. You're dealing with other people's lives, not fictional characters. As a bonus, an ethical approach also means you'll gain trust, and potentially get more and better interviews in the future as a consequence.

The real work starts back at your desk

Once the interviews are complete and you have your recordings, notes, memories, and impressions, it's time to get on with the writing. If it's your first ever biographical profile, you may experience a mini-crisis at this stage. You may wonder how, despite all your background research, preparation, and careful management of the interview, you ended up with such a disjointed mess of material rather than a story!

Keep calm. It's entirely normal. The material isn't the story. You, the writer, have the job of taking that raw material, selecting the best bits, putting them together in a logical order, and crafting the whole into an emotion-provoking and informative book. All your storytelling skills now come into play. This is where the real work begins.

Writing the leading paragraphs and chapters

At the outset, you should have chosen an angle that provided the focus for your research and your interview. That same focus will help you organize your material. A useful hint for getting started with writing up your book is to write the lead paragraph and the first chapter or two first. It'll help you set the tone, introduce the subject and the essence of their story. If you include a curiosity-arousing question — either directly or by implication — all the better for your readers and for you, as it will urge them to read on and guide you in what to write next.

The two best techniques for getting your lead paragraphs and chapters off to a good start include using a straight quotation from your interviewee, or an anecdote which embeds a contrasting past into the current context. These are both techniques which, done well, can work very hard for you, helping to sell your piece to the editor and hook the reader in to your story. For clarity, here are examples of each:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

1. Quotation

“I don't give a damned fig about what other people think. They like my work or they don't. That's always been my guiding principle.” These words, coming as they do from __________, the notorious avant-garde painter, don't surprise me. After all, that's why I'm here, perched on the edge of a chintz sofa in his traditional Ranch-style farmhouse: to find out why, earlier this year, he turned down one of the art world's most prestigious prizes.

This lead introduces the subject, the dialogue expresses his curmudgeonly personal style, and the contrast between his work as an avant-garde artist and the traditional formality of his home, intrigue. The question raised is, why did he turn down the prize and what were the consequences? Few readers would shrug the story off as uninteresting.

2. Anecdote

Max Hammond was the rising star of his high school hockey team, with an uncanny ability to slam the biscuit into the basket. Fast and fearless on the ice, good-looking, generous, and admired beyond the rink, he was destined to be a national player. But one December night, just a few days before the holidays, as Max and his best friend were heading home after practice, a drunken driver swerved off the road. Max was the lucky one. He only lost his right leg. His friend lost his life.

I meet him on his home turf, the local sports center in ___________, where he coaches disabled kids. His prosthetic leg stopped him from making the professional league, but it did little to quash his passion for the game. He looks up and waves, smiling, as he sees me enter the stands.

This lead introduces the subject, and the anecdote hits straight to the heart of the story. The contrast between his promising start and his tragic fate is stark. The questions raised are: How did Max cope with the death of his friend and the loss of his leg? When so many might have given up in anger and despair, what was it about Max that led him to turn the tragedy of the accident into a positive lifestyle helping others? Few readers would stop reading until they had answers to those questions.

Writing the body of your book

Once you've hooked the reader in with the lead paragraph and filled it out to the first few chapters, you must deliver on the promises you've implicitly made. In the main body of your book, which will run to tens of thousands of words, most likely, you must reveal all and tell the full story. The techniques for doing this are similar to those you'd use for a fictional story: highlight conflict and how the protagonist (in this case, your subject) overcame such obstacles; use selected emotion-provoking details in your narrative; plenty of pertinent, character revealing dialogue; look for a character arc, showing a transformation, where possible, toward a climax.

You'll find all the material you need in your recording, your notes, research, and your memories of the interview. The key skill here is to figure out what to include, what to gloss over, what to highlight, and how to order the information to shape a story. We'll be honest with you that we can't teach you how to do that. It's one of those things you must learn as you go. But if you keep your focus in mind and craft the truth into the shape of a good narrative, you shouldn't go far wrong.

Reading excellent biographies and profile books and analyzing them is worth all the time you spend on it. Pick them apart to understand how they work. Then, when you come to write your own, you'll have a good idea of what essential parts you must include and how they work together.

Wrapping up your profile book

No, we don't mean literally wrapping it up – we'll do that for you once we've printed it! We're talking about how and when you make the bridge from the main body of your story to the wrap-up or conclusion. We suggest that you select a juicy quotation, or a revealing snippet of detail to save back until the end. The idea isn't to introduce anything new or shocking at this stage, but to give the reader a memorable image which sums up the emotional heart of the story. When crafting the final chapter and paragraph, it's often a good technique to bring the narrative full circle, back to the opening anecdote, conversation, or observation, but help the reader to see and appreciate it in a new light based on the journey on which you've taken them.

Writing biographical profiles is a lot of work, but it can also be one of the most fascinating and rewarding writing projects you'll ever undertake. Once you've done a few, you'll ‘get the hang of it'. It's a great way to hone your interpersonal, storytelling, and writing skills. And if you've done your market research, you should find that you can make a reasonable profit in sales – although how to sell books as an independent author is another subject!

But you'll need to research the markets first to make sure you have a saleable book after all your hard work. If you want to write to print, publish, and sell your work, there's little point in writing anything — however good in itself — if there aren't readers out there who are keen to buy it. The most important step in becoming a successful independent author is the one most often overlooked: learning how to do focused market research.

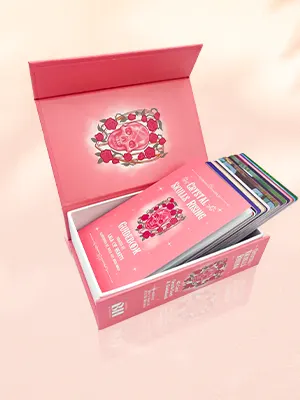

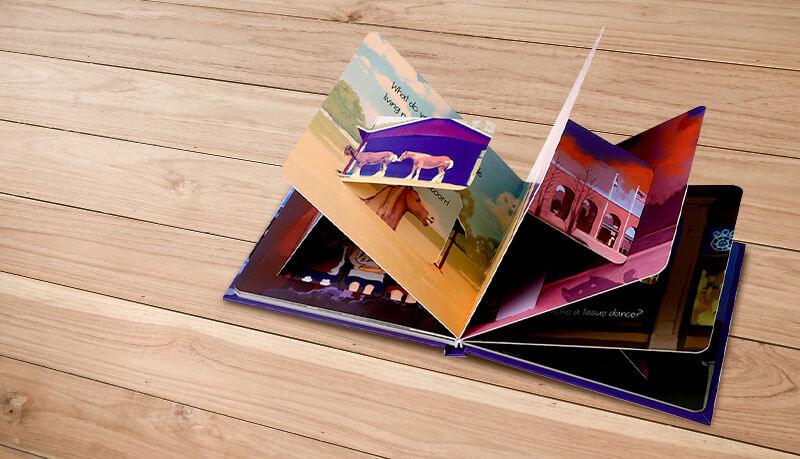

Once you've written your book and drafted the layout for the interior pages and the cover design, you'll need to print it. We recommend hardcovers with a dust jacket as the standard for a biography or profile book. It's the traditional way that mainstream publishers produce such volumes and it also meets reader expectations, making it easier to market. You'll also get a higher return on your investment on a hardcover edition than on a paperback. To find out all the technical details, you can start by visiting our main hardcover book printing page. When you're ready to print, or starting our working on the layout and design of your book, we'd love to hear from you to see how we can help. We have 30 years experience in the industry, an expert dedicated team of designers and printers, start-of-the-art printing facilities, and a worldwide reputation for excellence.

Talk to us. We're here to help!

If you have other questions or need clarification or help with any aspect of preparing your project for print, shoot us an email to [email protected] or just call us on +1 951 866 3971 and we'll be delighted to do all we can to help you.