We take you step-by-step from getting an idea to designing a prototype, testing, printing, and distributing the final product. Whether you need a game for your friends, club, or commerce, we've got your back.

One thing that all gamers have in common is a lively and original creative imagination. It’s the ability to problem-solve, imagine new possibilities, and ‘think outside the box’ — often, literally! — that sets gamers apart from the crowd. Most experienced gamers have their reliable old favorites to which they return again and again. Often, there’s also a strong desire to discover something new, innovative, and exciting; a game that gives you the same buzz that got you hooked in the first place.

But that game can be hard to find. So, it’s not surprising that sooner or later, a lot of gamers decide to make their own game. As the saying goes, sometimes if you want something to exist, you have to make it yourself.

You might want to figure out how to design your own board game for the sheer fun and satisfaction of sharing it with your friends, gaming community, or club. Or maybe you’d like to try selling it to a major game manufacturer. Perhaps you’ll strike out on your own commercial adventure as an independent entrepreneur. But whatever your objective, putting together a game that’s everything you dreamed of can be quite a steep learning curve. You’ll need to go through the following key stages to make your own board game:

- Getting and developing the idea

- Designing the layout, game play, and rules

- Creating a prototype ready for testing

- Game testing in live play situations to gather data and feedback

- Analyzing the results of the play tests

- Revising, refining, and improving the game based on your analysis

- Creating a new prototype and retesting

- Finalizing a full design including board, pieces, die, cards, and other components

- Printing and manufacturing the final game

It sounds like a lot of work, right? And it is. But it’s also a huge amount of fun, a creative challenge, and a massive satisfaction. Not to mention, if this is part of your game plan — pun intended! — a potential fortune, or at least a lot of kudos, as your game is bought, played, and reviewed by enthusiasts all over the international gaming community. Why not think big? But while you mull over the size, depth, and scope of your ambition, let’s dive in-depth into each step of how to design your own board game from scratch.

Getting and developing the idea

Before you can make a board game of your own, you need to have an idea. And not just any old idea, but a good one; an idea that will delight, intrigue, and surprise potential players; to spark their interest and get them keen and curious and ready to play. In many ways, coming up with a good board game idea is like coming up with the idea for a novel or a movie. For most gamers, getting loads of potentially exciting game ideas is not the hard part: it’s sifting through those ideas and refining them until you can put your finger on one and say, “This is it! This is the best idea; the idea that will be worth the time and creative energy needed to make it real.”

So, there are three aspects to this part of the process:

- Generating ideas

- Selecting ideas

- Refining ideas

We’ll work through each step in more detail now. But a quick word before we dive deep into all of this. Figuring out how to design your own board game is a personal creative process and unless your goals are purely commercial — in which case certain norms and standards might be expected — no hard-and-fast rules exist. Principles, guidelines, the benefits of other gamer-makers’ past experience, yes. But strict regulations, no.

So, feel free to accept or reject any of the ideas we’re going to look at and run with your own. That said, you don’t want to throw out the proverbial baby with the bathwater. Many of the guidelines are worth taking seriously, even if you end up adapting them. The best, most successful, and most enjoyable board games to play are usually unique takes on established ideas, rather than completely innovative in concept and design.

Generating ideas for board games

You may be buzzing with ideas already, or you may be struggling to come up with something that excites you and seems like it has enough going for it to make a great game. Either way, you can’t have too many good ideas! So here are our top tips for generating interesting and unique ideas for fun board games that may be worth developing.

1. Play as many games as you can

This one shouldn’t be too hard, right? It might seem super-obvious, but you’d be surprised just how many people want to create a new board game when they’ve never played anything other than the ‘classic’ games like Monopoly, Clue, Checkers, or Snakes and Ladders. The modern gaming scene is so much richer, more complex, and more developed than that. It can involve elements of strategy, role-play, questing, and team play; it can have aspects inspired by video gaming, movies, interactive adventures, and more.

It’s vital to play lots of games and explore the exciting variety of themes, mechanics, styles, and ranges available in the contemporary board gaming scene. That way, you’ll get an idea of what’s popular, what you enjoy most, and a deeper insight into what makes a game work. It’ll also help you accumulate a lot of knowledge about the ins and outs of board game technologies and methods which you can draw on when designing your own.

We recommend that you join a gaming club or go to your local games night as well as meet up with friends to play. Broaden your experience and cast your net wide. Gaming with others also allows you to gather useful insights into what other gamers like and don’t, and to get feedback on your ideas.

Keep notes on the games you play and the ideas they inspire. You can write them down in a physical pocket book, store them on your phone or tablet, or use a voice recorder. But we think pen and paper are the best for this as you can write and scribble and draw much more freely than with even the best note-taking apps. There’s also a lot of scientific evidence that ‘multi-sensory’ and ‘tactile’ note taking leads to better concentration and creativity. It can also be a good idea to take photographs of boards and other elements to remind you of the layouts and mechanics later.

2. Think about what's missing

As you explore the world of board gaming, always ask yourself what’s missing. What themes and ideas haven’t been captured in a good board game yet? Is there a group of people that aren’t represented well in game worlds and could your game change that? What about more interactive or multi-session games? Games that have flexible rules, perhaps, invented and adjusted by the players themselves? Or how about games for solo play, or board games adapted for teams or large groups?

While you’ll want your game to be enough like other games that it’s recognizable and doesn’t take a year’s study to understand the rules and objectives, your quest for something that’s also original and unique will come from asking questions and looking for what may be missing, as much as from taking careful notes of what’s already out there and working well.

3. Look beyond gaming for inspiration

While you’ll need a thorough understanding of popular — and not so popular — board games, it’s a good idea to look to other realms and genres for sparks of inspiration, too. Read books, watch movies, see live shows, listen to music, check out exhibitions, art galleries, and museums, explore sites of historical interest, get involved in sports. Any and all cultural activities will not only enrich your life but will trigger all kinds of cross-fertilized creative inspirations that could find expression in an idea for a board game.

4. Flights of fancy

One of the reasons we love games so much is that they offer us — like all the arts — an opportunity not only for fun and entertainment but also the chance to experiment with the impossible; to stretch the boundaries of reality out into the infinities of the imagination.

So, when you’re coming up with ideas for your board game, let your imagination fly. Let your players become astronauts venturing into the farthest reaches of outer space; or aliens invading Earth. How about dragons protecting their hoard of gold from marauding pirates? Or marauding pirates trying to steal a hoard of gold from dragons? Or both!

You could tip the usual good-guys-bad-guys paradigm on its head and have the players try to rob a bank, or steal and collect famous works of art from galleries around the world such as MOMA, Le Louvre, or The Tate. They could be rats trying to get as much cheese from the castle stores as they can, always with the threat of the cook’s chopper to contend with.

You could mash-up different genres, as Anthony Fankhauser and Rafael Jordan did when they wrote the TV show, Cowboys vs Dinosaurs or as Michael Crichton did, first with the novel and then the movie, West World. Why not introduce time travel into a detective game, shape-shifting into a racing game, aliens in a medieval fantasy setting? In short, vicariously living out impossible lives is one of the most fun aspects of any game play: so, release the eagle of your mind and let it soar on the outstretched wings of imagination!

5. Play, "What if?"

A great way to get ideas for games is to ask yourself the question, “What if?” It’s a technique that writers often use to get ideas for stories, too. You can use it to come up with completely new ideas or to reinvent old ones.

So, for example, you might be playing the classic board game, Clue, and you might ask yourself, “What if the murderer wasn’t only still alive on the board, but had the chance to kill again?” Answering that question could lead to a new, more complex, edgy, and challenging detective game than the traditional version. Or maybe you’ve just read Neil Gaiman’s American Gods or you’re a fan of Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackman series. You might ask yourself, “What if the old gods and goddesses of world mythology were real and still alive today?” Answering that question could lead to a whole new game concept to take the world by storm.

Whatever game you’re playing, wherever you are, whoever you’re with, whatever experience you’re having, ask yourself, “What if…?” And don’t forget to keep a note of your answers in your notebook, along with any sketches that may come to you for board layouts, pieces, cards, and the rest. Exploring all the possibilities — however improbable some of them may seem — is all part of the fun of working out how to design your own board game.

6. Information and education

While all board games should be fun, they needn’t be entirely trivial. In fact, one of the most popular games of all time that claims to be trivial — Trivial Pursuit — is actually very educational! There’s no reason why, if you have specialist knowledge or good research skills, and you’re passionate about a particular subject, you shouldn’t make a board game that’s both fun and informative or educational.

You could come up with games based on traditional subjects like history, biology, geography, math, physics, literature, and more. Or a game could be based on a hobby, a sport, or something like bird watching, travel, or collecting. Games based on finance, politics, entrepreneurial endeavors, and the world of work might be used in training and education in businesses and schools. Why not? And obviously, there’s a big market in educational games for kids, which help support numeracy and literacy in fun and exciting ways.

Selecting ideas for board games

Once you’ve got a good stock of ideas under your belt — or ideally in your notebook! — then it’s time to sift through them, test them, and narrow them down to a short list before you finally choose one to take to the next stage. That doesn’t mean that the others won’t still have value — and might be made into games down the line — so don’t throw anything away. Still, let’s take a detailed look at how to whittle the list down in the fastest, most fun, and creative way possible.

To get started, go through all your ideas and organize them. Can you group them together in like categories? For example, quest games, race games, cooperative games, solo games, team games, points games, etc. Next, think about the mechanics of the game ideas and group them again.

- Are there counters or figures which move across a grid according to the roll of a dice?

- Is the board fixed or is it constructed as the game progresses, offering new configurations with each session?

- Do the players need to collect objects, select cards, swap or exchange items?

- Must players work out clues and answer questions to further the objective?

- Do they need to memorize information and piece it together bit by bit?

- Will each player work alone or can they form alliances with one or more other players?

- Is every player in the game right to the end or is there a process of elimination whereby ‘the last player standing’ wins?

- Do players take turns ‘against the clock’ or is there a time limit on the whole game, a deadline by which the objective must be achieved or the game is lost?

- Will there be some elements of role-play or player-led invention and storytelling?

Those are just a few of the many possibilities. But asking these questions — even if you don’t have the answers right now! — will get you thinking along the right lines and help you begin to see which of the game ideas interests and excites you most and which will be the most practical to realize. Grouping and then sub-grouping your games in this way will help you to understand what kind of game mechanics, board layouts, and other practicalities may be involved when thinking about how to design your own board game.

Refining your board game idea

Now go through each grouping and ask yourself which idea most appeals to you at an instinctive level. Then, choose one that is interesting and unique, but won’t be so complex or impractical to make that it’s beyond your budget or realistic resources. It’s still not too late to change your mind, either, at this stage. So, don’t panic! You’ve still got all the other ideas stored away and you can come back to them later. In fact, it’s quite common in this part of the creative game making process to end up choosing elements from several of your original ideas and synthesizing them together.

Once you’ve got the list down to one — even if it’s a mashup of several ideas from your list — it’s time to refine the idea, to begin to put it to the test and see how it would work out in real play, to develop the theme, work out the mechanics, how people can win or lose, and all the physical design elements such as board layout, accessories, cards, dice, counters, figures, and so on. So, now let’s look at choosing and developing a theme because it’s an important step when working on how to design your own board game.

What makes a good theme for a game?

The best games all have a unifying idea or premise which informs the atmosphere, objectives, and mechanics of the game. This theme is often expressed as a setting or world — think of the manor house in Clue, or the streets of London or New York in Monopoly as classic examples; or the steampunk, medieval, fantasy, and space settings of several contemporary games — but it can also be more abstract.

Still, your game needs the idea to be embedded in a suitable theme first. Everything else will follow on from that. So, make sure to spend time exploring the possibilities before you settle on the best theme in which to express your idea.

What are themes for games?

Themes give context to the game and inform the roles the players take on and the aims they have to achieve. They give a logical background to all the other components of the game and help them ‘make sense’. They also provide the imaginative element which gives each game its distinctive atmosphere.

Getting the theme right is vital to getting your players invested in the game. It gives the sense of what the game is all about. It’s the ‘story’ if you like, and just like in a novel or a movie, it should be intriguing, suggestive, and inspire your players to get involved and find out what happens next. Here’s a list of the most common thematic types to get your brain buzzing with the possibilities.

Abstract — shapes, numbers, sets

Genre — geographical, historical, adventure, fantasy, mystery, etc.

Knowledge-based — general, literature, movies, science, sport, etc.

Puzzles — word games, mazes and labyrinths, picture matching, construction, etc.

These are just broad categories to get you thinking. You can break down or expand each of these — and any others you can think of — into dozens more. How ‘granular’ you want to get depends on how detailed, specific, and complex you want your game to be. It may help to look at some of the most popular games and analyze their themes.

What are examples of popular board game themes?

So, to help get a clearer understanding of the role of the theme in a good board game, here’s a list of 10 popular games — both classics and more contemporary — with the theme identified and explained.

Clue — this has the theme of a classic ‘locked room’ detective story, inspired by the murder mystery novels of Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The theme provides a clear objective: to find out ‘whodunnit’. It also informs the mechanics: searching for clues, asking questions, and getting the answer by a process of elimination.

Gunslinger — this is a Wild West themed game inspired by every western movie you ever saw from High Noon to The Magnificent Seven. It also includes elements drawn from history, based around the figures of Wild Bill Hickok, Billy the Kid, Wyatt Earp, and John Wesley Hardin. The objective is to survive a gunfight and the mechanics are detailed interactions between map boards, card decks, and character sheets.

Capes and Cowls — this is a light-hearted take on the superhero theme. The objective is to build a team of superhero allies — think X-men, Fantastic Four, and Justice Society — and bash the baddies. While dice are involved in the mechanics, it is largely a game of planning and strategy across a board layout based on the imaginary ‘Wyrd City’ in which all the action takes place.

Pirate’s Cove — this is a game themed around the adventures of the 16th-century buccaneers and inspired by the legends of Blackbeard and William Kidd along with swashbuckling pirate movies from Errol Flynn’s Captain Blood to Johnny Depp’s Pirates of the Caribbean. It has complex but easy-to-play mechanics combining many elements of both chance and strategy as you command your ship from island to island, fighting other pirates and amassing treasure.

Runebound — this popular board game, in its third edition at the time of writing, has a theme inspired by the fantasy worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien, David Eddings, Terry Brooks, and Robert Jordan — and brings the old school role-playing classics Dungeons and Dragons, RuneQuest, and Warhammer to a board game layout. As such, the mechanics are a mix of classic tabletop elements such as cards and dice and more interactive role play as your adventuring heroes seek to save the world from a marauding dragon and an undead king.

Risk — this game has a theme of world domination, inspired by the great historical campaigns designed to build empires and conquer the globe by a combination of strategy and military might. The mechanics include die-to-die battles, cards, and strategic advance over a grid. More complex versions with richer narratives have followed this one, but Risk remains the original classic of the genre.

Tikal — this game has an archaeological, jungle adventure theme inspired by the novels of authors such as H. Rider-Haggard and the Indiana Jones movie franchise. Players are explorers who must uncover lost temples and acquire the treasure hidden within. Mechanics involve a hexagon grid board which builds as play progresses, action points, territory occupation, and collecting items.

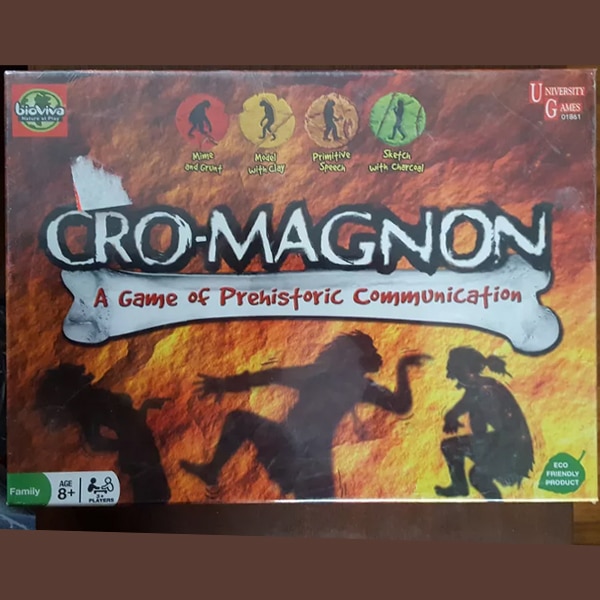

Cro Magnon— this “caveman” themed game is a light-hearted take on human cultural evolution. The mechanics are based around mime, wordplay, drawing, and acting — all against the clock — as each player tries to communicate to other members of the tribe in a prehistoric age before complex language had been developed. This is a fun, silly, interactive game geared more toward generating laughter than serious play.

Kingmaker — this game has an historical theme set in England during the time of the “War of the Roses”. Primarily a game of strategy, the mechanics use dice, a map board, cards and other features. This is a good example of a game which is both challenging and fun to play but also has an educational element as well.

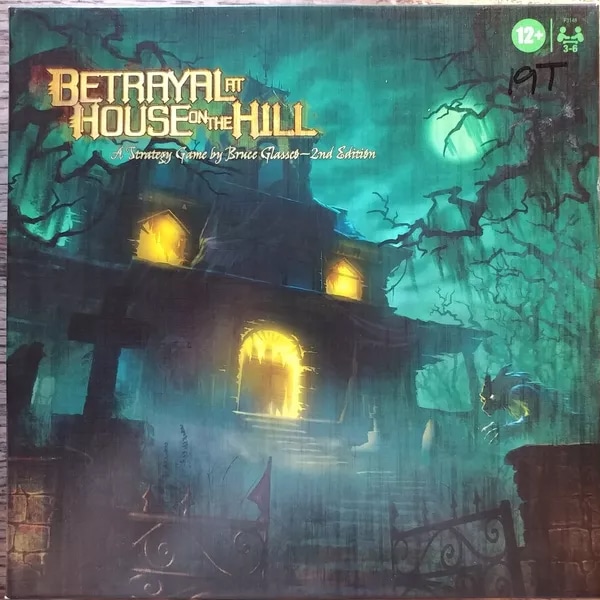

Betrayal at House on the Hill — a game with a haunted house theme inspired by everything from The Amityville Horror to Scooby-Doo and with references to the classic ghost stories of Edgar Allen Poe and M. R. James. The mechanics include a modular board structure which builds a new version of the house with each game, dice rolling, and eliminating players as the play progresses.

That should give you an idea of the importance of theme when you’re figuring out how to design your own board game and also — importantly — how theme influences the structure and mechanics of the game. But before you can develop your theme and devise the appropriate mechanics to support it, you need to choose one. Let’s look at how.

How do you choose a game theme?

As you’ll have picked up from looking at the games above, theme and mechanics are interrelated. But that’s not the only consideration you must take into account when you’re choosing your theme. Now you’ve picked an idea and started thinking about themes, you’ll probably have come up with several possibilities from which you need to choose one.

The selection process is important, but don’t over-stress about it as it’s never too late to switch back and change the theme or tweak it to make it a better fit. In fact, the early creative stages of how to design your own board game involve a lot of back-and-forth between the theme and the mechanics before you get a beautifully integrated whole.

To help you get to grips with this, here’s a list of ideas and questions for you to explore as you work out what will be the best theme to embody your idea. Again, there are no hard-and-fast rules, but you’d be wise to accept most of these questions as they’re the fruit of the labor of some of the finest game creators the world has ever known. As the saying goes, we stand on the shoulders of giants.

Characters and setting (protagonists and antagonists)

Whatever your game idea, the theme will help you understand how to frame the player and non-player character identities. So, for example, in a medieval setting, you won’t find racing car drivers or interstellar spacecraft. But if your basic game idea is for a race game, you could have charioteers or knights on horseback in a medieval-themed world. If you give it a fantasy edge, the protagonists could be dragon riders or wizards on flying carpets. Likewise, in a space-age themed game, your race could be between spacecraft.

In most games — as in all stories — there’s an antagonist. This can be a character — like a mafia boss, the general of the enemy army, a zombie horde, the murderer — or an obstacle such as the castle walls and moat, asteroids, hurdles and ditches, or monsters with an appetite for eating players, for example.

In each case, in our example here, the idea of the game (a race) is the same, but it’s embedded in a different theme: medieval, fantasy, space-age, whatever. And the theme dictates what kind of race it is, who does the racing, and what gets in the way. That is to say, the setting determines the nature of the characters; the protagonists and the antagonists. So, take some time to mess around with the thematic possibilities that would best embody and express your chosen game idea until you’re happy that you’ve got a good fit that makes the idea come alive and gives a rationale to the concept.

Movement and interaction between elements

Again, the theme will influence how long a game lasts, the kind and rate of movement over the board, and how the elements interact with each other. For example, fast moving space craft may need a board design that differs greatly from one designed for the slow progress of pirate ships or adventurers moving on foot. Likewise, in a medieval setting it may make sense that players can only interact — knights engaging in combat, say — if they land on adjacent squares but for gunfire or lasers, rules about distance and direction modified by the roll of dice may come into play. So, you can see — and we’ll explore this in detail later — that the theme embodying the idea also influences the mechanics of the game.

Storytelling and meaning

To illustrate in another way just how important theme is when devising how to design your own board game, think about a game stripped of its theme, leaving only an idea and naked mechanics. Take our racing example. The idea is simple: a race from A to B and the first to get there wins. I bet you can think of dozens if not hundreds of games based on this idea! Now, let’s add the mechanics: players roll dice to move forward across a board from one side to the other. Not very exciting, is it? Now, we’ll take this exact same idea and the exact same basic mechanics and add a few different themes:

- Players are knights who must get from the castle to the Wizard’s Tower to rescue the princess and win the Kingdom.

- Players are rabbits who must get back to the burrow before the fox catches them.

- Players are jockeys who must complete the racecourse before the other riders.

In short, then, “players need to move pieces from one side of the board to the other” is not interesting, but “players are superheroes who must fight their way through a zombie army to rescue the princess from the tower” is exciting! This is how theme makes a basic idea into an appealing game which sparks the imagination of the players.

Does the theme fit the goal?

At this stage, you need to start thinking about the goal of the game — and we’ll look at deciding on the rules for knowing when the game has ended and who has won in a moment — as that must be in keeping with the theme. Some common goals are:

- capture or destroy an object or location

- gain control of a territory

- collect a specified number of objects, cards, or points

- solve a puzzle

- find a hidden object

- a race against other players, the clock, or a non-player character

- completing a pattern or spatial relationship on the board

You will probably already have started to think about this and you’ll soon see that while many game goals can be interpreted successfully across a range of themes, several sit more comfortably in one rather than another. For example, finding a hidden object — treasure, or a lost tomb, perhaps — might better suit a fantasy or historical theme than a military or space age one. Likewise, capture or destroy an object or location — a castle, tower, space station, planet — could be adapted to several different themes.

Is the theme recognizable enough to be easily understood but unusual enough to be interesting and arouse curiosity?

This question mostly speaks for itself. While originality is important, you also want your game to be both recognizable and satisfying to your players. Choosing one of the established themes — such as those we listed above — is often the best idea. Then you can tweak and adapt it to give it a unique spin.

There’s a lot of similarity between game design and storytelling. After all, a game is a kind of interactive story. In a mystery novel, it might be unique to make the detective the murderer, but you risk turning the tables too far and rather than surprising your readers you may end up annoying them. So, take a recognizable theme for your game and find a new and interesting ‘take’ on it, but don’t mash it so far that players don’t understand what’s going on.

At the end of this first stage of the process of working on how to design your own board game, you should have selected a great idea and chosen a theme that will fit the idea well. You’ll also have begun to think about the game objectives and have started to consider the possible mechanics. So, now let’s look at how you can put the game together.

Designing the layout, accessories, rules, and winning conditions of your board game

Board game layout

The layout of the board, the game play, and the rules which govern the turns, actions, and winning conditions, need to be integrated so that they support each other and avoid conflict which can break a game. Fundamentally, there are two types of board: fixed and modular. A fixed board is, exactly as it sounds, a printed layout which doesn’t change. A modular board is made of separate elements which can be aligned or slotted together in a number of configurations.

Fixed boards are most common, but modular layouts are popular for adventure games and those influenced by traditional role-playing. The graphics printed on the board layout may include purely decorative aspects — always, of course, in keeping with the theme — but most will be functional. Of the many functional graphic elements, you may want to include:

- a grid of squares or other geometric shapes which define the space through which figures or counters move

- illustrations of locations such as buildings, trees, caves, islands, rooms, and so on

- buttons and badges with numbers to show points or prize objects

- written instructions that players must follow if they land on a given square, for example

- start and end points, safe zones, and anything else your game needs

You’ll also need to consider the size and shape of the board. So, there’s the square, an elongated rectangle, a circle, or an oval shape, which are the most popular. You can consider other shapes but they can become complicated to work with and expensive to produce. Give thought to the shape and size of the board as it will also influence the length of the game and how much can happen within the game world.

Depending on your game’s theme — and your budget — you may want to add three dimensional elements to the basic printed board. These can represent places and objects — buildings, bridges, traps, gateways, armory, and so on — or even, as in the classic Mousetrap! game, be mechanical. Just bear in mind that in most cases, complex three-dimensional structures are more challenging to design, expensive to manufacture, and rarely add more than a ‘gimmick’ to the game itself.

Board game components

Another important factor of the design is the way that the players — and other non-player characters — are represented on the board. These elements can be as simple as the classic Ludo counter — a plain, flat disk — or as complicated as the detailed, realistic figures used in war gaming. They may be abstract, like the ball-topped cones or ‘pawns’ in Clue; symbolic, like the old boot, the top hat, the car, and the Scottie dog in Monopoly; or realistic, like the 16th-century galleons in Pirate‘s Cove.

You may also need to consider dice, dice cups and rolling trays, spinners, tiles, cards, sleeves, wallets, purses, screens, holders, coins and other exchange tokens, gems, prize objects, character sheets, quiz cards, notepads, scoreboards, pegs, timers, and more. You’ll also need to write, design, and print the rule book. More about the rule book in the next section.

When you’re designing your board layout and all the other accessories — collectively known in the gaming world as ‘components’ — avoid going ‘over the top’ and trying to cram in every possible option. The best games are always those which have the minimum number of components necessary for smooth, well-paced play. Apply the rule of ‘Occam’s razor’ to your design.

William of Occam was a 14th-century monk who came up with an idea to aid the design of everything from architecture to scientific theories. His principle, known as Occam’s razor, states that the solution with the fewest elements — the simplest solution, in other words — is always the best one; as the simplest explanation is the most likely to be true. All components in a good board game must be necessary. Any component that doesn’t ‘pull its weight’ can probably be removed and the game will be better for it. So, use Occam’s razor to shave off any unnecessary elements that have crept into your game design.

Of course, all games must have rules. As our universe is governed, and our actions limited, by the Laws of Nature, so the world of a game and the actions of the players must be governed and limited by a set of clearly defined and laid out rules. Getting the rules right for a game is a challenging — but often enjoyable — business. Let’s look next at how you do it.

How do you design rules for a board game?

First of all, why do we need rules? Well, because — just as in the real world — if there were no rules we would have only random events and total chaos. We have an idea, a theme, and some notion of the mechanics of the game and what’s at stake for the players. So, now we need a set of rules that define and — most importantly — limit what players and other active components in the game can and cannot do.

You could say that rules serve to regulate the operation of the game world’s mechanics so as to make achieving the objective both possible and difficult. Your game’s rules must serve three purposes:

- to limit and guide player actions

- to explain what is and isn’t possible

- to make explicit the consequences of actions players take

It’s a big ask, right? But as always, the basic rules of any game — however complex the play itself— should be, in themselves, simple. Rather like the small handful of fundamental physical constants in our universe that govern everything from the charge of an electron to the birth and death of galaxies.

Rules and rule books

Now, let’s make an important distinction at this stage; the difference between the rules and the rule book. You will know and understand the rules once you’ve finalized them. But to finish all the steps needed when you’re going through how to design your own board game, you’ll need to summarize all the rules in a rule book. The key to a good rule book is how clearly and succinctly it communicates everything that the players need to know in order to enjoy the game.

All good rule books, except for the very simplest of games, will combine text and graphics composed in a reader-friendly layout. As much thought and care must go into the design of your rule book as goes into the rules themselves. You’ll only fully understand the game’s rules once you’ve experimented, play-tested, revised, and changed them through several rounds. So, while it’s a good idea to keep plenty of detailed notes, leave the actual writing, design, and printing of your rule book as the last thing you do.

Also, remember that in some styles of games none of the rules may be written up in a rule book. They may be printed on the board, or on a series of instruction cards, or just on the box. But for most games of a complexity beyond tiddlywinks, backgammon, or checkers, you will need a rule book to explain how to play your game.

Rules come in many shapes and forms and govern movement, gains and losses, combat, and more. Here are a few invented examples of the kinds of rules with which you’ll most likely already be familiar. These are just to get you thinking about the sorts of rules that may be best for the game idea and theme that you have in mind.

- Each player takes it in turns to roll the dice. The number they get is the maximum number of spaces they can move in one go. This is a typical movement rule.

- If a player lands on a blue square, they must pick a card from the ‘lucky dip’ pile and follow the instructions on the card. This is a rule which introduces an element of the unexpected into a player’s turn, which may help or hinder their progress.

- The first player to complete building a castle, wins. This is an example of a rule which gives the ‘win condition’. More about those in a minute.

- Any player who lands on the cave mouth while trying to escape, wakes the dragon and must replace all their treasure on the hoard. This is an example of a ‘consequences’ rule.

Balance and clarity in board game rules

It’s impossible to give a one-size-fits-all solution to the problem of devising the best possible rules for your game. Each game is different. But there are some good general guidelines to follow when working all this out which will help keep you on track and make sure that your game rules are clear, logical, and balanced, leading to a fun and satisfying experience for your players.

Taste your pudding

In the end, when it comes to how to design your own board game, it’s all down to what does and doesn’t work in real play. And that’s why we recommend that you do as much play testing at every stage as you can. Whether you’re working everything out in your head, scribbling it all down on a notepad, or using some fancy-pants software to help you, you never really know which rules are best until you play them out.

Most would-be game makers have a hunch that they’ll need to play test. But many don’t realize just how much! Still, this should be one of the most exciting parts of creating a brand-new board game, right? The more you play test, the faster and more effectively your game will evolve and the simpler and clearer your rules will become.

Calibrate the conditions

Rules are there in part to make it more difficult for your players to achieve the ‘win condition’ and end the game. So, think about a simple race from one side of the board to the other. If there were no rules, then a player could just place their counter at the other end in their first move and declare themselves the winner!

So, rules come in to play; like limiting the distance a player can travel in one turn by introducing a dice roll, or building in forfeits and setbacks if they land on certain squares, or tests and challenges they must pass to progress. The fun of any game isn’t so much achieving the win condition as doing so despite all the difficulties and obstacles that the rules put in your way.

But the level of difficulty that the rules introduce must be carefully calibrated. If your game is too difficult, your players will become frustrated and confused. If it’s too easy, they’ll be let down and disappointed. Check out the reviews of new games released into the market. One of the most common causes of a negative review is that the difficulty level wasn’t right for the age and expectations of your players.

Destiny, dexterity, or decisions?

All games lie along a spectrum between pure luck and strategy or skill — which may be manual, intellectual, or interpersonal — and it’s vital to get the balance right for your game. As a guideline, the younger your players, the more likely it is that the game will depend on luck and the older they are, the more opportunity you have to introduce elements which rely on players solving specific problems, making the right decisions, or being fast enough or observant enough to break through a ‘rule barrier’ and progress toward the win condition.

Options and opportunities

There’s not much fun in a game where players don’t need to make any choices. So, build in a number of options they must select from at various points in the play and make sure that those choices are meaningful. The best way to make choices meaningful is to stack them with potential opportunities and consequences.

If a player must choose between the door on the left and the door on the right, for example, don’t have both doors lead to the same chamber! Maybe the door on the left takes them back to the start while the door on the right takes them forward to the next challenge. Or, if both doors take them into the next chamber, maybe the door on the left makes them invisible for the next three turns, while the door on the right leaves them as they are. And you can improve these choices by making sure that there are clues to which is the right decision.

Not all games have such strong narrative elements, but the choices must still be there. So, maybe at a certain point a player must choose between making a regular dice roll to advance — a safe but slow option — or risking a ‘chance card’ which could rocket them forward or lock them down for a couple turns. Another example might be the good ol’ ‘double or quits’ opportunity which you could reinvent in any number of ways in line with your game’s theme and mechanics.

The ways that you build these options and opportunities into your game are probably infinite. It’s down to your creative imagination and the specifics of the game you’re making to decide. But the key point is that a good game should give the players at least the sense that they can make decisions, take risks, and influence outcomes, rather than everything being decided for them.

Confused? Cut!

Remember Occam’s razor? When you play test your game with others, if they complain consistently of any rules that are too hard to understand, remember, or that require too many complex calculations, or are in any other way confusing, you probably need to cut those rules out. Or at the very least, find a way to make them simpler. One of the most common errors that rookie board game designers make is to over-complicate the rules. Keep it clear, keep it simple. Rules should make play smoother, more exciting, and more fun. Anything that works against that must go.

At-a-glance rules for making good rules!

- Rules should be as clear and simple — and as few — as possible

- Rules should make getting to the win condition harder but not impossible

- Rules should make the game easier to understand and play, not the opposite

- Rules should align with the idea, theme, and mechanics of the game

- Rules must be appropriate for the age and skills of the players

- Rules must meet player expectations of game-play such as length, difficulty level, etc.

- Rules must always be tested and revised before being written into the rule book

- Rules should never be confusing

- Rules should be fair to all players

- Rules that are not needed to make playing the game possible should not exist

Creating the 'win condition'

Now, the final and fundamental question you need to answer when thinking through how to design your own board game is, how do you win? How the game is won — and so when it ends — is known as the ‘win condition’. The win condition will be influenced by the theme and mechanics. In a race game, the player who gets to the finish line first is the winner. Other games may involve construction — like our finish-building-your-castle example above — while others may be about solving a crime or destroying an enemy base, or any number of other things. But whatever the context, the win condition must be precise and unequivocal. There must be no doubt.

While we’ve come to it last, the win condition of your board game is something that you need to start thinking about early on. Making a board game isn’t really a linear, step-by-step process. You’ll need to jump back and forth from one aspect to another and tweak something here in response to a change there, and slowly bring it all together. But getting the win condition right is vitally important to the success of your project.

There’s no definitive list of win conditions— believe us, we’ve looked — as each game maker and each game always have their unique elements. But to help you start thinking along the right lines, here are few typical examples of win conditions from imaginary games. You’ll be able to think of many more once you get started.

- A process of elimination. Let’s say it’s a combat game based on an ancient Roman gladiator theme. The win condition is to be the last surviving gladiator.

- A race to the end. This could be themed around formula one, chariot racing, or salmon heading back to the breeding grounds, or… anything where you need to get from A to B as fast as possible. The win condition is fulfilled by whoever gets there first.

- Completing a set. This could be an archaeology themed game, where the players are trying to locate and open tombs in search of lost treasure. The winner could be the first player to collect x number of artifacts and get them safely back to the museum.

- Highest scores. Let’s say the game is inspired by a big business theme in which the players must accumulate profits, buy out other businesses, and increase their stock market value. The winner could be the first player whose business reaches a stock market value of x million dollars.

- Gaining ground. How about a military strategy game in which each player’s army must advance to occupy a certain territory or number of territories? The winner is the player whose army gains control of the area, perhaps by having a piece on each square or by blocking off access by other players.

That’s really just a tiny selection of popular possibilities. Literally hundreds, if not thousands, of other possibilities exist. The key is that the win condition must be beyond argument, achievable, and in keeping with the idea, theme, and mechanics of the game. And some games can have more than one potential win condition in an either/or framework, or combine two conditions, as in our made-up archaeology game above, where the players must collect a number of objects and get them back to base.

How to write the rule book for a board game

Now you’ve done most of the hard work. You’ve come up with a great idea for your board game — or more than one! — and chosen a fantastic theme, thought about the mechanics of play, figured out the board layout and the other components, and worked out the rules. During all this, you’ve tested and refined everything. Now it’s time to write the rule book.

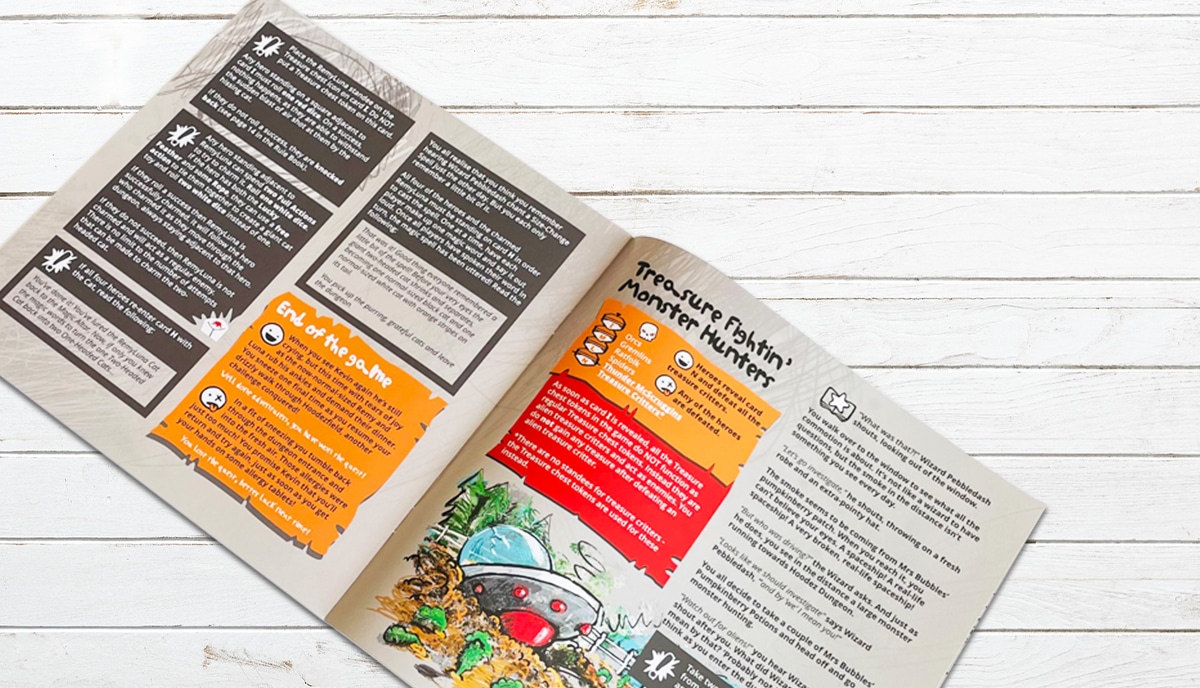

So, here’s a very important point to get started with a good rule book isn’t just a list of rules; it’s a manual that helps players enter into the spirit of the game and understand how to play. So, like any other book, it should have an almost narrative element to it. It should embed the rules — with examples where they’re helpful — in the themed story world of your game. Composing your rule book in this way serves three purposes:

- It gets the players excited and imaginatively involved

- It makes the rules explanations more interesting and memorable by providing color and context

- And it communicates more effectively by providing relatable examples of the rules working in a play setting

As we noted before, several rules may be built in to the game mechanics and components — instructions on the board itself, for example, or on game cards or other elements. But the core rules that make the game possible should be in the book. Now, there are several factors to consider that will help you make a board game rule book that looks great, is logical and easy to follow, and communicates all the rules with clarity and precision.

- The order of the rules must be logical in progression

- The rules should be embedded in a narrative structure drawn from your game’s theme

- The rules should be illustrated with engaging and informative graphics

- The best rule books use summary boxes, bullet points, sub-headings, white space, and diagrams to enhance the layout and make it easy to read

- The keyword topics and most important headings and subheadings should be in ‘bold’ or in different colors to make them easy to find

- If your rule book is long — as it might be for a long-play role-playing or strategy board game — it could be useful to have an index for quick look-up in case of need a memory jog or to resolve a dispute

A rule book may be short or long — role-playing rule books often have hundreds of pages — but they should always be as short as possible. And while examples are useful, there’s no need in most cases to include an example of every aspect or stage of play. It’s usually best to leave rule-related, but not rule-dependent functions, of the game — such as strategies and approaches to problems — for the players to discover according to their own wits. That’s part of the fun of playing, after all.

How to make a prototype board game

As you should have understood by now, going through all the stages of how to design your own board game is what we call an iterative process. It means going through the same or similar stages over and again several times, refining the results a little more with each pass. The same applies to generating your prototype board game. You can — broadly speaking — break it down into three distinct sub-stages:

- The ‘minimum viable product’ version with which you test the player experience

- The ‘mock up’ version with which you test the look, feel, and practicality of the components

- And the ‘final prototype’ stage which puts it all together in a version that’s very close to how you expect the finished product to be

Prototyping and further testing go hand in hand. And that’s another reason to follow this three-stage process. It’s common — and totally understandable — to think that you’ve got the best game idea in the world, have fully integrated it with the theme and aligned all the mechanics, and so what more could you need at the prototyping stage than a beautiful, printed board with professionally made components just as the ‘real thing’ will be?

But the truth is that no game is ever as ready as you think it is until it’s been thoroughly retested in the initial stages of prototyping. So, follow this good advice, and don’t expend too much time and too many resources until you’ve smoothed everything out. Now, with that in mind, let’s look at each stage of the prototyping process in more detail.

The minimum viable product stage

The concept of ‘the minimum viable product’ is the brainchild of the entrepreneur and originator of the ‘Lean StartUp’ philosophy, Eric Reis. It’s a simple and practical idea: at first, create the most pared down version of a new product that will still work and test it on consumers before creating the final thing. It’s a good principle to borrow for prototyping your board game.

As the prototyping and testing process will inevitably lead to further tweaks and changes — no matter how well you’ve prepared at all the previous stages — you need to invest minimally and keep each element easy to change, replace, or eliminate. So, following the minimum viable product principle, create your first prototype as a handmade craft product. Use regular office paper, cardboard from boxes, colored pens, sticky tape, and found objects like bottle tops and children’s toys.

It doesn’t need to be pretty or look professional at this point. It just has to have all the components represented so that the game can be played. Once you’ve built out this approximate physical version of your game, you can play test it on players who represent your target audience. And at this stage, the feedback you’re looking for is all about the gamers’ experience. Ask them:

- Were the rules clear and easy to understand and implement in play?

- Was the pace of the game right, or was it too fast or too slow?

- Did the game last long enough, or was it too short or did it drag on?

- Was it exciting, intriguing, and fun?

- Were there any points in which the players felt bored or left out?

- Any other feedback about the experience of play?

Make detailed notes of all this feedback and repeat the test play as many times as you can with as many different groups of players as possible. Then, once you’ve gathered all your data, collate it all together. You’ll begin to see patterns emerging: rules, mechanics, and components that everyone agrees work well and others that hinder the flow of play, or leave someone out, or no-one understands.

Armed with this information, make such changes and adjustments as needed, and then retest. At this early stage, there could be a lot of changes to make and some of them could be radical. That’s another reason why you shouldn’t invest money and resources in the physical game at this stage: it’s a lot easier to ditch cards that are just numbers and character names written in Sharpie on scraps of paper than a beautifully designed and printed set made on high-quality stock with a gloss finish!

The 'mock up' version

At this stage the mechanics should have been refined and be working well to give the players a fun and positive experience of the game. Now, it’s time to make a more developed version of the prototype which begins to represent more accurately the ‘look and feel’ of the finished product. A good way to go forward at this stage is to get together components borrowed from a number of different games you own or can get hold of to stand in as ‘proxies’ for the finished products. But you’re looking to get as close as possible to the kind of artwork, styles, visual look, and general atmosphere of what you’re aiming for.

Once you’ve created a mock up like this, it’s time to play test again. This time, though, as you should be confident of the mechanics, you need to ask a different set of questions. For example, you want to know:

- Do the players like the look and feel of the game?

- Does it fit with their expectations based on the idea and theme?

- Is there anything they feel doesn’t work well or looks out of place?

- Are the characters — if represented in your game — relatable?

- Do they get a sense of the atmosphere of the game?

- Do the components work together to encourage and enhance imaginative involvement with the theme?

- Do the players feel that they’re ‘in the game world’?

Again, you’ll need to play test through several iterations with different groups of players, collate the data you gather, and make any tweaks needed. Although, you’re getting very close to the finished product now, so the changes needed should be fewer than in previous stages. Once this round is complete, you can go on to make a finished prototype — one that will be barely distinguishable from the final game product.

The final prototype

There isn’t much difference between the final prototype and the finished game. In fact, depending on your ultimate objectives and the size of your budget, it may be identical. At this stage, you’ll be designing and printing a board with all the artwork, creating printable and non-printable components, designing, writing, and printing your rule book, and creating a beautiful custom printed box for it all to go in.

We’ll go into this in more detail in just a moment. But this is the version which you’ll either play with if you’re creating a game just for your friends or a small club; it’s the version that you’ll take to conventions, trade fairs, and present to potential publishers if you’re looking to strike a deal with a games company; and it’s the version that you’ll approve and order in larger numbers if you’ve decided to self-publish and distribute your game as in independent producer.

Either way, it should be a game that looks good, works well, and of which you can be proud. You’d be surprised how few folks who start out with a good idea for a game actually get to this stage. Or, having done it, perhaps you wouldn’t. After all, you know now just how much work goes into making a great game that people love to play!

How to get your board game made

When it comes to the time to actually manufacture your game — or your finished prototype — you’ll need to get in touch with a custom offset printer with experience in making custom board games — and, among others, that’s us, by the way. We won’t lie to you: it’s a complex process and will take a while. But the more detailed preparation you’ve done in advance — by going through the steps we’ve outlined here about how to design your own board game — the easier and more straightforward it will be.

It’s a good idea to start talking to your printer as soon as you get to the first stages of the prototype testing phase. You may, if you have the relevant skills and software, make your own illustrations and designs for all the components of your game. In most cases, however, you’ll need to engage the services of a professional illustrator or graphic designer. We have our own in-house designers but you’ll still need to provide the basic artwork for them to work with.

Once you start the process of creating the templates and files ready to print your game and manufacture the components, expect a lot of back-and-forth between you and the printer. That’s normal and ensures that the product we’re collaborating on is working out exactly as you, the customer, want it at every step of the way.

Once all the files are agreed and checked and you’re happy with everything, we’ll manufacture and send you a prototype for approval. Once you’ve approved the prototype, you can order a run for however many game units you want to manufacture and we’ll create, quality-check, package, and deliver them to your chosen destination.

How to sell your board game: pitching to game publishers and self-publishing

Once you’ve made your own board game, there are two basic options for you if you want to sell it. You can either try to get a mainstream board game company to buy it from you or you can set up on your own as an independent self-publisher and distributor. Which you chose depends on your assessment of your ambitions, what you want to get out of selling your game—other than money, obviously—and the knowledge, skills, and other resources you have available (or can learn and raise) to invest.

The core difference between self-publishing and selling your game to a mainstream publisher is that in the first case, you have complete creative control of your project and you get to keep all the profits you make on eventual sales; in the second case, you no longer own the game, so the publisher can change it, adapt it and develop it as they want and you’ll only get a ‘royalty on sales’, which is typically about 5% of net profits. But, it’s a little more complex than that. So let’s have a look at the pros and cons of each option.

Pros and cons of pitching your board game to a mainstream publisher

Successful self-publishing board game designers often crow about their achievements and will tell you that the ‘big boys’ will only rip-off your idea and keep most of the money for themselves. Failed self-publishing game designers will tell you it’s too much hard work and you’re throwing good money after bad and should take your game to the mainstream. But the truth probably lies somewhere between these two extremes. Certainly, a deal with mainstream publishers can be advantageous.

- The company that buys your game will pay for any further development, manufacture, printing, storage, distribution, and delivery

- Once sold, you can forget about it and let the royalty checks (small as they may be) roll in while you dive into your next game design

- If they decide to ‘get behind’ your game in a big way, you stand a chance of getting rocketed into the big time and potential millionairedom (despite the 5% royalty)

- While your name won’t be writ large on the box, if you want to get a reputation in the business, there’s more chance with all the exposure you’ll get from a big company, such as interviews, reviews, and being a guest panelist at game conventions

If you’re really not much of a ‘business head’ and would rather hunker down and design new games than handle all the other aspects of running your own show, then going mainstream could be your best option. But there are plenty of potential disadvantages, too. So, let’s look at those now.

- You no longer own your game

- You give up creative control

- You might not earn much (most games are not ‘big hitters’)

- It could literally be years before you see your game in stores

- Making a successful pitch is notoriously tough

So, it’s not all a proverbial bed of roses. For most game people, it’s that loss of creative control that bites the hardest. And if, having given that up, you then see someone else getting rich on the back of your efforts while you only earn dimes and cents, that’s not a good feeling. So, how about self-publishing?

Pros and cons of self-publishing your board game

We’ll be honest with you, self-publishing your board game is not for the faint hearted. You need a set of skills which go far beyond creative design: fundraising (unless you already have the capital to invest), communications and IT (for your Kickstarter campaign, website, and blog), book keeping, accounting, and project management, marketing and promotion, and a lot of self-belief, a bunch of support friends, and a cast iron determination to succeed. If that describes you, you could enjoy the following benefits from self-publishing:

- Complete creative control of your project end-to-end

- Potentially faster turnaround from design to market

- Potentially bigger profits (and so more to invest in future game projects)

- A good chance of making a return on your investment without needing to sell multiple thousands of units

But of course, even if you’re cut out for it, personality and skills-wise, self-publishing aren’t all buttercups and daisies, either. For example:

- You shoulder all the risks, financial and otherwise

- It’s very hard work and can be exhausting

- You’re no longer a hobbyist: you’re in business with all the responsibilities that go with that

But don’t jump to conclusions either way. Remember that many people do—usually after a lot of rejection—get ‘a break’ and make a successful career working with the big game companies. And others—often after climbing a steep learning curve—become successful self-publishing game makers who never look back. It’s a personal decision, but not one to take lightly.

Ready to make your pro-level custom board game?

As soon as you’re ready either to make your final prototype to hawk around the cons and tout to game publishers—or if you’re ready to print your first run of games for your Kickstarter backers or to take to market—talk to us. We have decades of experience in the industry. We’re a friendly bunch, too, with a genuine focus on customer care. Get in touch for an informal chat, to find out how we can help you, or to get a competitive and no-obligation quote for your project. We look forward to playing our part in your board game’s success!

3 thoughts on “How to Design Your Own Professional Board Game: A Complete Guide for Beginners”

why is it so long

Well, it is very clearly explained, to the smallest detail. That needs a lot of space.

Hi Max and Braden, well, yes, it is a long one, this! But we really wanted to make it easier for new board game designers to find all the information they need gathered in one place without having to invest in a lot of expensive books and courses to piece it all together. And as Max says, that does need a lot of space. Thanks for reading and sharing your thoughts, guys!